02 December 2016

Critical infrastructure protection – governance around the world

As pertinently noted in [1], critical infrastructure not only relies upon physical infrastructure such as roads, plants, buildings, pipelines, but also cyberspace and the informational and communicational means supporting this cyberspace. This blurs the lines of responsibility and duty for critical infrastructure security between different authorities, whose activities do not traditionally overlap, and involves a large number of parties in the protection processes.

The effectiveness and timeliness of interaction between the various contributors to the different aspects of critical infrastructure security are crucial for handling incidents on time and preventing significant damage. In the longer term, well-adjusted management of this interaction is necessary to develop an integrated and coherent security capacity in critical infrastructure.

This research is intended to find out which approaches to cybersecurity governance on the national level are currently in place around the world (especially in the sphere of protecting critical infrastructure against cyberattacks), and estimate the current maturity of cybersecurity governance in different countries. This may help us (and other large companies) to focus on the most important issues and fill in the gaps of critical asset protection on the strategic level.

The need for critical infrastructure protection oriented on public-private collaboration

The specific requirements of diverse domain areas related to critical infrastructure need special consideration, with the setting of their own security goals and forcing the responsible authorities to be guided by these goals. Moreover, security control in most solutions should be adjusted according to the constraints of the physical assets and processes. In many cases, this adjustment requires close cooperation between the security authority and the facility stakeholders.

Arranging this level of cooperation is a particularly pressing issue for privately owned facilities. To address this, the government has to develop public-private relationships in the context of critical infrastructure protection processes.

All these factors highlight the essential nature of critical infrastructure protection governance for the development of key critical infrastructure domain areas both in the short- and long-term perspective, as well as for finding the approach that best fits the needs of every particular domain area.

In this regard, it is interesting to examine the indicators of cybersecurity governance maturity for different countries using the available studies on development and the current state of applied cybersecurity practices in these countries [2] [3].

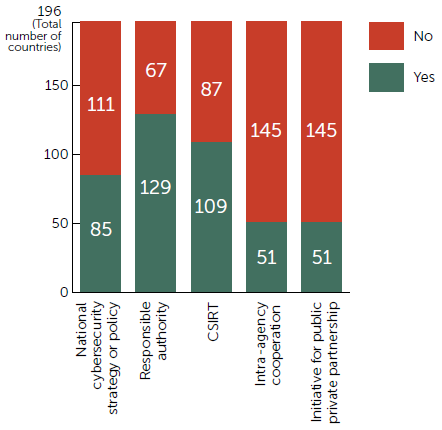

We discovered the Cyberwellness Profiles for the countries around the globe, provided by ITU [2]. The following parameters were taken as a basis for the evaluation of governance strategy:

- Does the country have an officially recognized national cybersecurity strategy or policy?

- Does it have an officially recognized agency coordinating national cybersecurity (and implementing the strategy if it is defined)?

- Does it establish and support an officially recognized national CERT or CSIRT?

- Does it define a national or sector-specific program for sharing cybersecurity assets within the public sector (intra-agency cooperation)?

- Does it define a national or sector-specific program for sharing cybersecurity assets within the public and private sectors (public-sector partnership)?

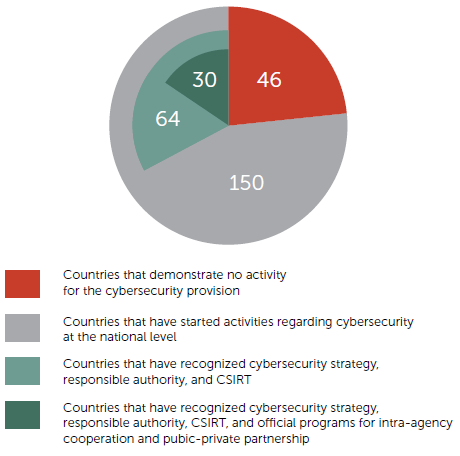

The analysis of these parameters for the 196 countries that ITU has described in its Cyberwellness Profiles is demonstrated in the Figure 1.

- 85 (out of 196) countries around the world have an officially recognized national or sector-specific cybersecurity strategy; 111 don’t

- 129 countries have an officially recognized agency coordinating national cybersecurity (and implementing a strategy if it is defined); 67 don’t

- 109 countries have an officially recognized national C(S)IRT, while 87 don’t

- 51 countries have a national or sector-specific program for intra-agency cooperation, while 145 don’t

- 51 countries have a national or sector-specific program for public sector partnership, while 145 don’t

Fig. 1. The Allocation of Cybersecurity Governance Related Indicators for the Countries around the Globe

As we will see further, the combination of these parameters determines the level of maturity of cybersecurity governance for the state. However, the type of governance strategy stated in the comparison below is determined not by one or more of these parameters, but by the role of the main authority responsible for critical infrastructure protection and its engagement in the process of protecting critical assets against cyberattacks.

The following responsibilities may come under the remit of this responsible authority:

- Regulate protection activities

- Regulate intra agency cooperation

- Foster public-private cooperation

- Issue secondary legislation

- Identify systems of vital importance

- Define relevant sectorial technical rules and measures

- Define and possibly support relevant processes (e.g. incident notification)

- Support evaluation and certification according to established criteria

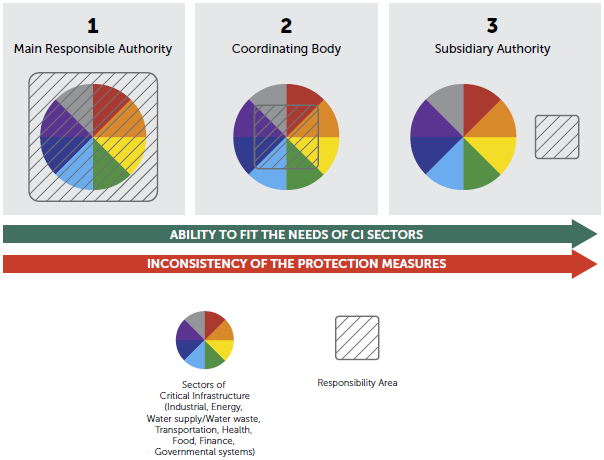

A survey on applied practices for critical infrastructure protection reveals three main types of governance strategies*. In most cases, following one of these types is the result of joint evolution between regulatory and operational authorities acting in the area of national security, the cybersecurity domain and specific sectors of critical infrastructure, rather than the result of a conscious governmental choice.

While each of the described strategy types has its own advantages and disadvantages, similar results can nonetheless be achieved by each particular approach if the intrinsic issues are addressed properly. The following comparison is intended to identify these issues and how to address them.

* – While all of the states mentioned below have their own national strategy for critical infrastructure protection pursued by the government, we do not intend to compare these strategies only. This is more of a comparison of possible ways a particular state may go, disregarding the existence of an officially approved strategy document.

Main responsible authority

This is initially a centralized approach. There is a ministerial department or governmental agency responsible specifically for cybersecurity. Other departments may consult the leading authority or participate in appropriate activities, but they cannot impact decisively on regulatory processes. Examples of this approach can be found in Germany, Italy, the Czech Republic, and Estonia.

Cybersecurity measures are well-documented and usually applicable to all domain areas with strictly stipulated exceptions.

The leading authority concerned with cybersecurity issues on the governmental level is usually also responsible for the protection of critical infrastructure against cyberattacks. For this purpose, this authority formulates the directives and recommendations (in accordance with legislative requirements), sets up the rules certification criteria, provides appropriate guidance documents and supports long-term governmental programs (for example, UP Kritis in Germany [4]).

The main advantage of this approach is that it provides a holistic approach to critical infrastructure protection in a usually well-established regulatory and operational framework. This approach facilitates the balanced development of security practices for various sectors.

Such a centralized approach is written, for example, into the Cyber Security Strategy for Germany: “The protection of critical information infrastructures is the main priority of cyber security. They are a central component of nearly all critical infrastructures and are becoming increasingly important. The public and the private sector must create an enhanced strategic and organizational basis for closer coordination based on intensified information sharing.” [5]. The Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) is the main national authority responsible for the protection of critical information infrastructures at the federal level. Its activities are supervised by the Federal Ministry of the Interior. While critical infrastructure protection is seen as a networking task involving diverse bodies at various levels, all appropriate cybersecurity programs and initiatives are coordinated by the BSI [3].

In the Czech Republic, the overarching authority is the National Security Authority (NSA), which is responsible for cybersecurity as well as the protection of classified information, security clearances and the cryptographic authority. Protection of critical infrastructure is handled by the National Cyber Security Center that is an integral part of the NSA. In the event of cyber security incidents, the NSA acts as the main authority and coordinative body for the relevant bodies and agencies (including different public and private CSIRTs). The relevant entities can be bound by the decisions of the NSA during a cyber state of emergency or when dealing with the threat of a cybersecurity incident. The NSA supports and advises operators of critical infrastructure in emergency responses and provides forensic analysis if requested [3].

Some countries may not have the dedicated regulatory authority, but instead have an official CERT or CSIRT with broad competence and extensive powers in supporting security in national cyberspace. One example is Latvia. Its national CSIRT (the Information Technology Security Incident Response Institution of the Republic of Latvia – CERT.LV) shares the coordinating role with the state security service, the Constitution Protection Bureau, both operating under the Ministry of Defense. These bodies collaborate in the assessment and management of the current risks to critical IT infrastructure. The Constitution Protection Bureau has the right to examine personnel related to ensuring the operation of critical infrastructure, request the CERT.LV to conduct inspections on the infrastructure to determine the vulnerability and security risks of the relevant critical infrastructure, and give recommendations to the stakeholders for the elimination of any detected deficiencies. It may also issue recommendations to state administrative institutions who supervise the critical infrastructure owners. Furthermore, the Bureau, together with the CERT.LV, periodically informs the National Information Technologies Security Council regarding current threats to critical infrastructure [3].

In principle, active collaboration between a regulatory authority and a national CERT or CSIRT is an indicator of a regulator’s openness, their awareness of short-term industry needs and a willingness to support public-private relationships by the stated means.

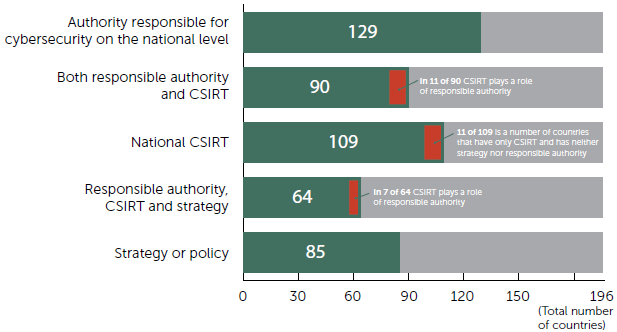

Analysis of ITU’s country Cyberwellness Profiles [2] shows that from 129 countries that have an officially recognized national cybersecurity authority, 90 also have CSIRT. For 11 of those 90 countries, CSIRT is also the responsible authority. If we consider only those states that have an officially recognized cybersecurity strategy (or policy), the number decreases to 64. These are the states with a relatively mature approach to cybersecurity governance (see Figure 2).

Fig. 2. The Global Situation with Main Cybersecurity Governance Indicators

Disregarding the organizational form of a single responsible authority, this governance strategy traditionally has trouble with building public-private partnership. Representatives of a particular critical infrastructure domain may doubt the cybersecurity experts have the appropriate competence in this domain or do not clearly recognize the links between cyberattacks on informational infrastructure and possible physical damage. Private facility stakeholders may have little incentive to disclose information about security incidents.

Without the initiative of each particular sector, development of security measures may rely on misleading objectives, setting up requirements that are difficult to meet due to domain constraints, and ignoring existing practices for this domain. To address this issue, some states at the forefront of protecting their critical resources and facilities from cyberattacks are trying to diversify the approach to critical infrastructure protection by giving more focus to every identified sector and involving valuable stakeholders of those sectors.

For example, the German regulator BSI implements the aforementioned UP Kritis program. As noted in [4], “UP KRITIS, however, also deals with topics which go beyond the IT area in order to maintain and strengthen the availability and robustness of critical infrastructure. In order to ensure a comprehensive protection of critical infrastructure, physical protection and IT security must be jointly developed and implemented. The cross-sectoral cooperation between industry and the state within UP KRITIS has become a success. The organizations involved cooperate on the basis of mutual trust. They exchange ideas and experience(s) and are learning from each other with respect to the protection of critical infrastructure. Together, all parties are thus finding better solutions. Within the framework of the UP KRITIS, concepts are developed, contacts established, exercises held and a joint approach for (IT) crisis management developed and launched.”

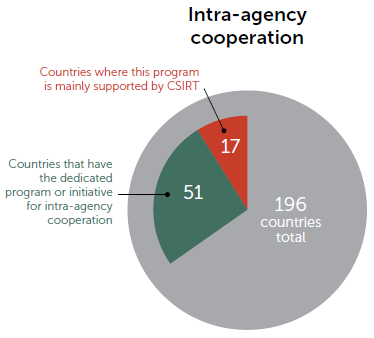

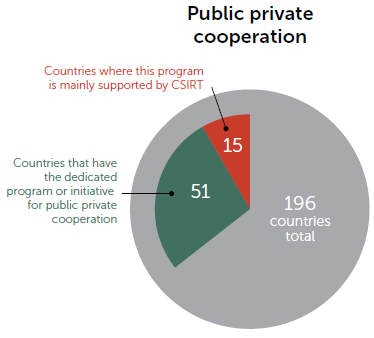

According to ITU [2], 51 countries have put in place the official program for intra-agency cooperation. Also, 51 (but not the same) countries established the national program for sharing cybersecurity assets in the public and private sectors. In both cases, for almost one-third this was done with CSIRT participation: in the former case, CSIRT facilitates the program in 17 countries, and in 15 countries in the latter case (see Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Allocation of PPP-related Programs and Initiatives for the Countries

Coordinating authority comprised of several bodies

In some other countries protection of critical infrastructure is under the remit of several collaborating departments, inter-ministerial groups or committees. These collaborating authorities usually play the role of coordinating body. This is the case in Austria, France, Poland, Finland, Australia, Canada and many other countries.

For this approach the titular responsibility for critical infrastructure protection may still lie with a single authority, or be explicitly stipulated for a number of authorities.

In Austria, the Federal Chancellery of Austria and the Federal Ministry of the Interior share responsibility for critical infrastructure protection on a strategic level. Steering and coordinating the different agencies is the responsibility of the Cyber Security Steering Group (CSSG) composed of liaison officers for the National Security Council and cyber security experts of the ministries represented in the National Security Council. The Chief Information Officer of the Federal Republic of Austria is also a member of this body. Representatives of other ministries (particularly those responsible for organizations and enterprises that are subject to or affected by control measures) and of the Austrian federal provinces will join the Steering Group as required to address specific issues. Representatives of relevant enterprises will be involved in an appropriate manner. On an operational level the coordination structure is divided between an “inner circle” and an “outer circle”. The inner circle includes several public agencies, the most significant of which are the Cyber Security Center, the Cyber Defense Center, GovCERT, MilCERT and the Cyber Crime Competence Center (C4). The outer circle includes private organizations such as several sector-specific CSIRTs and the national CSIRT (CERT.at) [3], [6].

The coordinating body for critical infrastructure protection in France is the General Secretariat for Defense and National Security (SGDSN). The SGDNS is an inter-ministerial organization and is under the authority of the Prime Minister of France. ANSSI is an interministerial agency under the strategic guidance of SGDSN’s Strategic Committee. These are the two main agencies for all aspects of critical infrastructure protection and there are no other formal forms of cooperation with other public agencies. ANSSI cooperates with the private sector in 18 different working groups on matters such as the identification of systems of vital importance, the definition of relevant sectorial technical rules and measures or the definition of processes (e.g. incident notification) [3].

In Poland, the main responsibility for critical infrastructure protection lies with the supra-ministerial Government Centre for Security (RCB) while all appropriate activities are supported by cooperation forums between public agencies and CI operators. Meetings of representatives from relevant ministries to discuss issues of critical infrastructure protection take place every few months. In addition, an expert group of relevant representatives from government institutions meets every two weeks to draft recommendations for the Secretary of State [3]. The Cyberspace Protection Policy of the Republic of Poland [7] explicitly separates actions concerning the security of ICT infrastructure from the efforts aimed at protecting critical infrastructure, the provisions for which are contained in the National Critical Infrastructure Protection Programme. The National Security Strategy of the Republic of Poland [8] in particular notes: “The protection of critical infrastructure constitutes an obligation of operators and owners supported by public administration capacities”.

In Finland, there is no single authority responsible for critical infrastructure across all sectors. Finland’s Cybersecurity Strategy declares that “most of the critical infrastructure in society is in private business ownership. Cyber know-how and expertise as well as services and defences are for the most part provided by companies. National cyber security legislation must provide a favourable environment for the development of business activities” [9]. The National Cyber Security Centre Finland (NCSC-FI) at the Finnish Communications Regulatory Authority (FICORA) is the main responsible governmental agency within the communications sector. National Emergency Supply Agency (NESA) is responsible for the security of supply, including ensuring the continuity of national critical infrastructure. Other sector-specific authorities include the Energy Authority, the Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority, the Supervisory Authority for Banking, the National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health, and the Transport Safety Agency.

As can be seen from this review, this strategy type is oriented towards a partnership of the state and authorities well-versed in particular domain areas of critical infrastructure. These authorities in turn are responsible for building the relationships with enterprises and privately owned facilities that are significant for the domain.

For this approach the security objectives for various sectors can be set with less effort, thus overcoming the natural excessive diversity of critical infrastructure. At the same time, establishing the requirements for the security measures in this case shall also be performed within each particular sector. Without common requirements or metrics, the cybersecurity-related procedure and measures for different sectors will be legislated and applied in an unchecked and non-uniform manner. This causes a potential problem with the maturity of critical infrastructure protection on the state level.

Subsidiary authority

In the rarest case, the state may follow a “doctrine of subsidiarity”. This means the complete transferring of responsibility to the critical infrastructure owners, as in the case of Ireland. Ireland’s Cyber Security Strategy states that “because of the diverse ownership and operation of various ICT systems, the State cannot assume sole responsibility for protecting cyberspace and the rights of citizens online. The owners and operators of information and communication technology are primarily responsible for protecting their systems and the information of their customers” [10]. There is no leading or designated authority for critical infrastructure protection in Ireland.

Another country implementing the principle of subsidiarity is Switzerland. It is believed that the stakeholders know their own processes and systems best and should therefore be in charge of identifying all hazards for these processes and systems; they should also be in charge of deciding on appropriate countermeasures. The government supports this process where it can. Accordingly, critical infrastructure operators are responsible for their own security, but the state offers subsidiary support. The Reporting and Analysis Centre for Information Assurance (MELANI) is the national information exchange hub between the private and public sector. It can be described as the main authority for the protection of critical infrastructure in Switzerland during a cyber incident.

The quest for compromise

The main responsible authority is capable of setting the framework within which cybersecurity across all sectors will be enhanced uniformly. A principal concern is that the uniform approach does not fit the specific needs of every particular sector.

On the other hand, the approach based on cybersecurity self-regulation is ideally suited to the diversity of critical infrastructure needs, apart from the fact that in this case incidents, some of which may be quite serious, cannot be avoided.

The approach to cybersecurity governance that involves several departments playing a role in the coordinating body for critical infrastructure protection seems to be the optimal one (see Figure 4). In practice, it is not always possible to avoid both the rigidity of the authoritarian approach and the disorder intrinsic to self-governance.

Fig. 4. The Approaches to the Governance of Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity

There is an in-between approach in which the regulating authority may partially shift the responsibility onto the critical infrastructure stakeholders (owners of facilities, operators, legal possessors). The state control of implementing protection measures is only enforced for vital facilities and organizations (those which, if compromised, could cause severe consequences on a national level). This approach is used, for example, by the French regulator ANSSI mentioned above [11]. The measures recommended for critical infrastructure are applicable, with some concessions for facilities with medium level criticality, but penalties for disregarding security measures may only be imposed in the event of an incident. The responsibility for the protection of non-critical facilities lies exclusively with their owners.

Security is thereby considered to be a matter for the market. The serious drawback of this is the lack of motivation for small and medium-size companies to worry about security until they’re seriously affected by an incident. In practice there has been very little use of protection against cyberattacks at industrial, water and power supply facilities, manufacturing plants, and other traditionally “non-cyber” sectors which, nonetheless, currently deploy the full range of informational and communicational technologies including use of the Internet.

Both the full and subsidiary roles of the state in support of critical infrastructure protection are supplemented by the active involvement of security researchers, companies and suppliers of security solutions. This is the third side of the widely discussed public-private partnership (the first and second being the state and specific critical infrastructure sectors) that maintains an awareness of current security threats across the industry and develops security solutions that address all specific needs.

Conclusion

An informed choice of governance strategy for critical infrastructure protection is possible only for those states that are just about to go down this route. According to ITU [2], [12], official CERTs or CSIRTs are functioning in most states around the world, and these teams usually act as the leading authority regulating critical infrastructure protection, or are linked to this authority. 150 countries have already started some activities with regards to cybersecurity on the national level (they have established a responsible authority, put a cybersecurity strategy in place, or established a CSIRT). 64 countries have a strategy, a responsible authority and officially recognized CSIRT. 30 of those 64 countries have recognized programs for intra-agency cooperation and for public-private partnership (see Figure 5). These states demonstrate a mature approach to cybersecurity governance and make a special effort to protect critical infrastructure from cyberattacks.

Fig. 5. Cybersecurity Governance Maturity for the Countries around the Globe

However, this comparison of governance strategies may be useful for the timely elimination of the drawbacks identified for each strategy type. Successful tactics and methods from one critical infrastructure protection approach may be transferable to another approach in order to achieve optimal operational results.

Without a doubt, security companies, independent CERTs and security researchers have progressively taken on a substantive role in supporting public-private partnership in critical infrastructure protection processes.

The exchange of state experiences with the subsequent updating of legislation, operational and technical practices (via standardization and the adoption of international roadmaps) facilitates better and faster strengthening of critical infrastructure security around the globe.

[1] Dr. Frederick Wamala (Ph.D.), CISSP. The ITU National Cybersecurity Strategy Guide. September 2011.

[2] ITU home page. ITU-D. Cybersecurity. Cyberwellness profiles.

[3] CIIP Governance in the European Union Member States (Annex). January 2016.

[4] UP KRITIS. Public-Private Partnership for Critical Infrastructure Protection. Basis and goals.

[5] Cyber Security Strategy for Germany.

[6] Austrian Cyber Security Strategy.

[7] Republic of Poland. Ministry of Administration and Digitisation, Internal Security Agency. Cyberspace Protection Policy of the Republic of Poland.

[8] National Security Strategy of the Republic of Poland. 2014.

[9] Finland’s Cybersecurity Strategy. Government Resolution 24.1.2013.

[10] Department of Communications, Energy & Natural Resources. National Cyber Security Strategy 2015-2017.

[11] ANSSI. Cybersecurity for Industrial Control Systems. Classification Method and Key Measures. 2014.

[12] ITU home page. ITU-D. Cybersecurity. National CIRTs world-wide: 102. 2016.