01 July 2019

How we hacked our colleague’s smart home, or morning drum & bass

- An offer you cannot refuse

- Potential attack vectors

- File system image analysis

- Vulnerability scan

- The “Attack”

- Conclusion

In this article, we publish the results of our study of the Fibaro Home Center smart home. We identified vulnerabilities in Fibaro Home Center 2 and Fibaro Home Center Lite version 4.540, as well as vulnerabilities in the online API.

An offer you cannot refuse

The backbone of any technology company is made up of tech enthusiasts – people who eat, sleep, and breathe it, whose passion for experimenting, including on personal devices, leads them to interesting results. The idea for this study was suggested to us by a colleague of ours, a system administrator in the past and now vice-president of the company. Fibaro Home Center was installed at his home, and he kindly gave us permission to dissect it.

Fibaro is a rather unique company in some ways. It started operating in 2010, when IoT devices were not yet widespread. Today, the situation is different. According to IDC, in just a few years the number of IoT devices will hit almost one billion. Fibaro Group’s plant in Poland already makes about one million different devices a year – from smart sockets, lamps, motion sensors, and flood sensors to devices that directly or indirectly influence the security of homes fitted with them. Moreover, sales of Fibaro devices for 2018 in Russia grew by almost 10 times against 2017. The company clearly plays a significant role in the IoT device market, so a study of Fibaro smart home security is very timely indeed. And when our colleague offered his home as a guinea pig, we could hardly say no.

It is our hope that this article will attract more researchers to the world of IoT, since the growing army of IoT devices requires ever more resources to analyze them. We also hope that the results of our research will catch the eye of companies that produce IoT devices, since errors like the ones we found are best addressed at the code audit and device testing stages.

The challenge we thus faced was to attack the system of someone we knew. On the one hand, this simplified the task, because we did not have to prepare a test bed (the system includes a fairly wide range of different devices). Yet on the other, it complicated it, because the host knew about the impending attack, and had every opportunity to secure his home against the “intruders.”

Potential attack vectors

Before examining the vulnerabilities detected, we will describe our analysis of the attack surface of the Fibaro smart home and consider each of the attack vectors.

Reconnaissance stage

Just like real cybercriminals, we started with a little intelligence and information gathering from open sources.

Smart home equipment is rather expensive, but there is no need to own a specific device to get the required information about it, since Fibaro publishes extensive details of its devices online. The FAQ section on the company’s website provides some interesting facts. For example, Home Center can be managed directly from home.fibaro.com or even via SMS. So clearly, when Internet access is available, the system connects to, and can be controlled through, the cloud.

The website also divulges that Home Center manages Fibaro devices using the Z-Wave protocol. This protocol is often used to automate home processes, as it has greater range than Bluetooth and lower power consumption than Wi-Fi.

Another tidbit is that if the network already has some kind of smart device that does not belong to Fibaro (for example, an IP camera), Fibaro provides various plug-ins to integrate the device into a single complex and manage it from Home Center.

Our colleague greatly simplified our task by providing a static IP address through which we could gain access to the admin panel login form.

Admin panel login form

A scan revealed that only one port accessible from the outside was opened at this IP address and it was forwarded on the router to the Fibaro Home Center admin panel. All other ports were blocked. The presence of an open port goes against Fibaro’s security recommendations (see item 10). However, if our colleague had used a VPN to access Home Center, the lack of any entry points to start analysis would have put an end to our study before it had begun.

Perimeter overview

At the reconnaissance stage, information from open sources (more precisely, from Fibaro’s official website) was sufficient to piece together several attack vectors that could be used against our colleague’s home.

Attack via Z-Wave

This attack can be carried out in the immediate vicinity of the device. The intruders need to reverse-engineer the code of the Z-Wave communication module, for which they need to be within range of a device operating on the Z-Wave protocol. We did not go down this route.

Attack via the admin panel web interface

As is known, the smart home system has an admin panel for device management. This means that there is some kind of backend and data storage on the device in question. Most often, due to the lack of RAM and persistent memory in embedded and IoT devices, the server role is performed by PHP or CGI (which run alongside a lightweight web server), while the file system or file database (for example, SQLite) acts as the storage. Sometimes, the server-side logic is wholly processed by a web server, which takes the form of a compiled binary ELF file. In our case, the software stack consisted of PHP, Lua, nginx, a C++ server, and lighttpd, while data was stored in both an SQLite database and a special section of the file system.

The fact that the admin panel operates through an API written in PHP encouraged us to continue this line of enquiry. To investigate the admin panel for vulnerabilities using white-box testing at this stage, we had to get the admin panel source code and the firmware of the smart home itself. This would provide a clearer understanding of its architecture and the structure of the logical processes inside it, such as scanning and downloading/installing updates.

Attack via the cloud

This type of attack can be carried out in two ways:

- By attempting to gain access to a device via the cloud having already access to similar Fibaro device,

- By attempting to gain access to the cloud, without access to any Fibaro device.

This vector implies testing the software logic, which is often located on the vendor’s servers. As we found out at the reconnaissance stage, Home Center can be managed through home.fibaro.com, a mobile app, or SMS. Even if you do not have a static IP address, your device will be accessible from the Internet. This means that the device connects to a server (most likely the vendor’s), which can allow the attacker to gain access to another smart home through the vendor’s common network.

The differences between (a) and (b) will become apparent when we examine the device architecture in more detail. At this stage, suffice it to know that we need to somehow collect data about what common functionality the devices have in terms of the cloud.

File system image analysis

Let’s skip the description of how we found the image of the file system for the required device (we describe different ways of getting device firmware with examples as part of our IoT/embedded device vulnerability search training).

Our examination of the file system turned up some interesting facts.

Web API

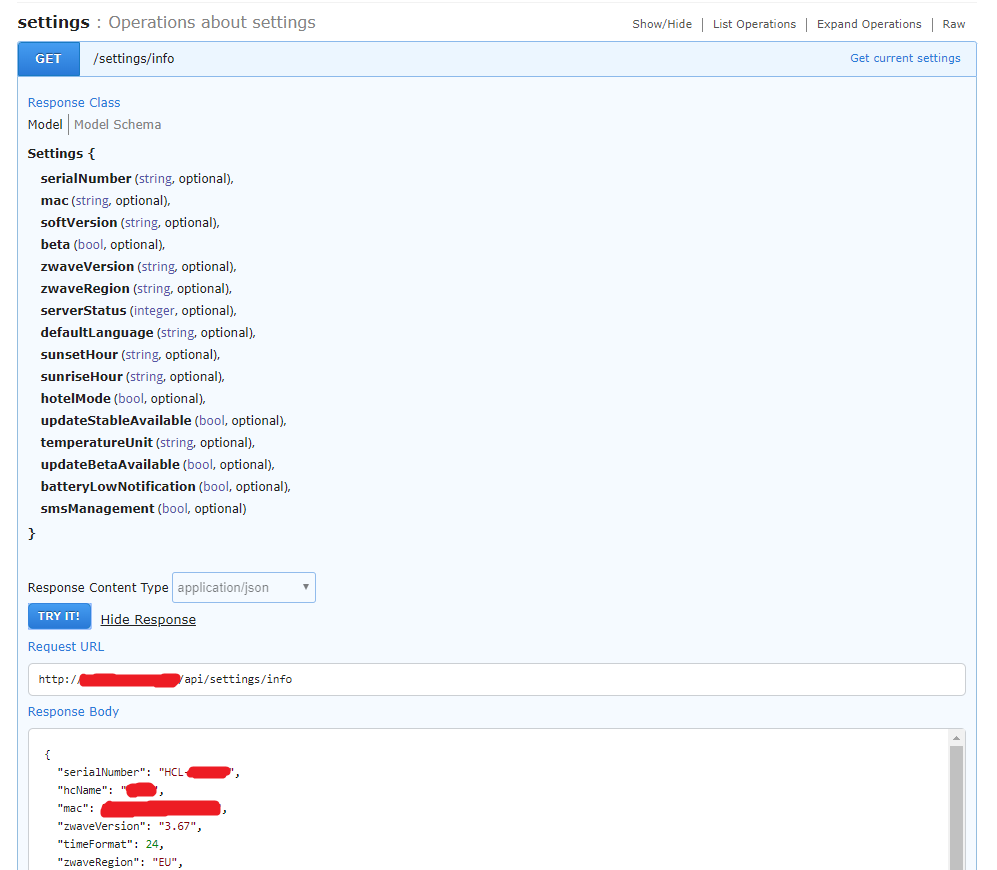

The web server has a fully documented API that describes methods, parameter names, and the values they can take in a request. However, it turned out that to get any significant information, it was necessary to log into the admin panel.

The only information that can be obtained without authorization is the device serial number.

Access to the documented API through the web interface

Also, it can be seen in the nginx web server configuration file that some requests are proxied to a local server written in C++, and some are proxied to lighttpd, which executes code in PHP using mod_cgi. These PHP request handlers are called “services”

Simplified nginx server configuration

Services

As already stated, the majority of API requests are handled by a C++ binary server. However, for unexplained reasons, the developers singled out part of the logic (rebooting the device, restoring factory settings, creating a backup copy, and much more) and wrote it in PHP.

The web server written in C++ accepts all requests from nginx, and we have no direct access to it. This significantly narrows the attack surface for this web server – we have no option to send a randomly generated HTTP request to it.

Therefore, the part of the logic written in PHP is of great interest to us, since it is just about the only entry point for a possible attack.

Serial number and hardware key

Each device has a serial number and a hardware key, which are used to authorize it in the cloud. Each time a device wants to perform an action that is somehow connected to the cloud (for example, send an SMS or email to the device owner, upload a backup copy to the cloud, download a backup copy), the device sends an HTTP request to the server with the serial number and hardware key as parameters. These are checked in the cloud for compliance in the database. If authorization is successful, the action is executed.

As we already know, the serial number is not secret: It is fairly easy to get by means of an API request. Moreover, the number is not long. The serial numbers we encountered correspond to the regular expression (HCL|HC2)-(\d{6}), which is a small enough space to brute-force.

The hardware key, meanwhile, is secret and individual for each device; it is stored in a special section of the file system that is mounted during device bootup.

However, only the device serial number is used for scanning and checking for updates. This makes it quite straightforward to download any update from the cloud by serial number.

Threat of hardware key theft

A device that stores personal user data must be made as secure as possible against intrusion. To increase the level of protection, device developers sometimes deprive the owner of superuser rights in the system. In this case, the owner becomes an ordinary, non-privileged user able to perform only actions allowed by the developers. Sometimes, however, this approach does not work, because if the owner wants to tweak or fix something in the device (for example, a vulnerability in the phone’s code), they will not be able to do it independently. They will need assistance from the device developers, who can release an update with a fix, but not as quickly as one would like. Therefore, an alternative approach involves developers giving owners superuser rights, together with the responsibility for their use.

Both approaches have their strengths and weaknesses, and the question of which is better is a good topic for debate, but not today.

Fibaro’s developers decided not to give Home Center owners superuser rights and extra responsibility. Therefore, we viewed options to elevate privileges in the system from the admin panel as full-fledged vulnerabilities.

In the threat model we built for Fibaro Home Center, the priority is to protect the hardware key. The device has a function for sending notifications to the smart home owner in the event that their participation is needed to resolve issues reported by smart home equipment. Any hardware key owner can send messages, and the list of recipients who the owner of a particular hardware key can contact is not controlled in any way.

Messages from the cloud come from the address SERIAL_NUMBER@fibaro.com, where SERIAL_NUMBER is the serial number of the owner’s device. It can be assumed that not all device owners remember their Home Center serial number, and are not vigilant enough to check it. They are likely not to notice the substitution of the serial number in the sender’s address; the fact that the message was sent from the @fibaro.com server will be enough. And they will perform the actions recommended in the message.

Since the problem of extracting the hardware key from the device’s persistent memory is in most cases a question of time, it might be an idea for developers to change the mechanism for sending messages and SMS.

Scenes

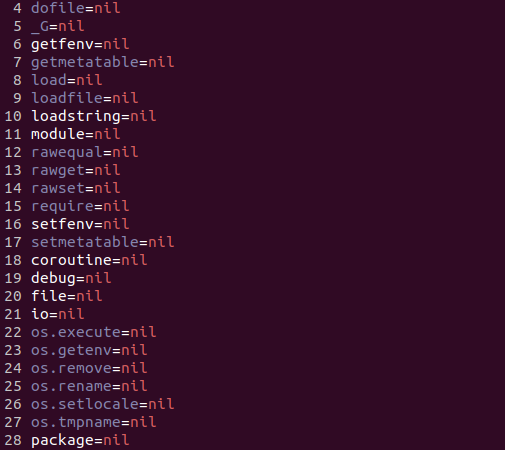

In the Fibaro Home Center admin panel, it is possible to create “scenes” – behavior scenarios composed of blocks or scripts written in the Lua programming language that are executed under specified conditions.

Lua provides the option to create an isolated environment in which the programmer can execute arbitrary scripts in Lua without going beyond it. The language is also known for having various vulnerabilities that make it possible to escape from this isolated environment. A good example is a recently discovered vulnerability in Lua 5.0.3 in the bytecode verifier module, which formed the basis of a CTF challenge. In the description, the author states that the vulnerability was originally exploited on a “VPN SSL device” that that they were investigating as part of their work.

Unfortunately, we were out of luck: On the device that we examined, a newer version (5.2) of the Lua interpreter without the bytecode verifier module was installed, and none of the known simple methods of escaping from the Lua sandbox was available. In our case, the task of finding vulnerabilities in the isolated environment was reduced to searching for vulnerabilities directly in the Lua interpreter. This task is quite time-consuming, so we decided it would be irrational to pursue this vector.

Lua isolated environment

Plug-ins

Many plug-ins for Fibaro Home Center can be used to manage devices that may not belong to Fibaro. This feature adds a very interesting research vector: Can a cybercriminal with access to a device controlled by Home Center through plug-ins attack Home Center and gain access to it? Within the framework of this study, we decided to postpone work on this vector and focus instead on vulnerabilities more likely to bear fruit.

Cloud communication

To communicate with the cloud, the device performs several steps:

- It gets the IP address and port to which it should connect,

- It establishes an SSH connection with the server,

- It forwards SSH port 22 to the specified port.

Thus, the Fibaro control center can connect to Home Center via a cloud server using a private SSH key to execute any command sent by the home owner, for example, by SMS or via the website.

Authentication nuances

An administrator password salt was not individually generated for each device, but strictly defined in the PHP code. If an attacker wanted to gain access to all Fibaro devices, their goal would be made a lot easier as a consequence. The cybercriminal could download all saved backup copies of all Fibaro smart home users, and then find identical hashes corresponding to identical passwords. The most common password matching the most frequently occurring hash could be brute-forced.

The scenario whereby an attacker builds rainbow tables for a given salt is possible in a targeted attack against all users of Fibaro systems. This is another argument in favor of generating an individual salt for each device.

Vulnerability scan

The first thing we looked at during our study was the part of the API implemented in PHP.

It would have been very interesting for us to test the methods that lay behind login, but without the ability to sign in, this research vector would not have yielded any results, since we could not call the methods we needed.

We investigated practically the only entry point available to us, and found nothing. It seemed that the study had reached a deadend, but then we decided to study the attack vector via the cloud.

Access to the cloud through which the smart home is managed (i.e. home.fibaro.com) was also unavailable to us, so we could only collect information about the cloud from scripts on the device that accessed it. As a rule, requests to the cloud were made from the device using the command-line tool cURL. Of all the requests, the most interesting were those for uploading backup copies to the cloud and downloading them from the cloud to the device.

AUTH BYPASS

After testing the cloud methods for processing requests from the device, we discovered a vulnerability linked to an authorization error allowing an intruder to list the backup copies of any user, upload backup copies to the cloud, and download them without having any rights in the system.

This problem occurred in the PHP code most likely as a result of incorrectly processing a scenario in which the passed value of the hardware key was set to null.

We rated this vulnerability as critical because it allowed access to all backup copies that were uploaded to the cloud from all Fibaro Home Centers. As will be shown later, using a backup copy and a remote code execution vulnerability in the admin panel, it is possible to gain full control over Home Center without interacting with the owner.

Remote code execution

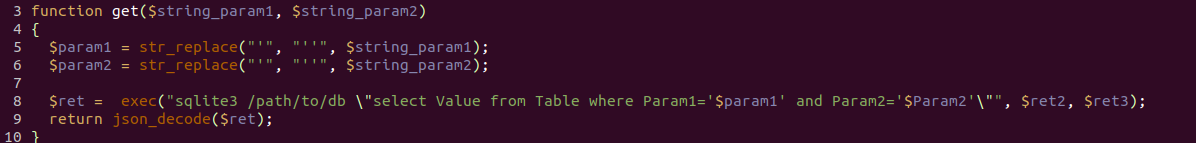

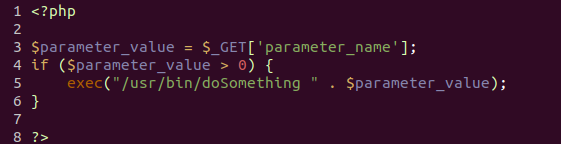

Several remote code execution vulnerabilities were related to weak implicit typing in PHP. Let’s consider a simplified PHP code snippet in which we found a vulnerability:

Simplified PHP code snippet

On Fibaro devices, a significant part of device management is implemented using bash scripts, which in turn invoke command-line utilities for direct execution of required actions in the system. Some of these executable scripts are invoked directly from the PHP code using the exec command. Since in the above snippet the user-controlled parameter is subsequently included in the command-line arguments, it needs to be filtered. If it is not possible to avoid executing bash scripts, the best solution is to not interpret this line in the bash shell and to run this command in an execve()-style way through the pcntl_exec function. However, due to the weak typing in PHP, and the fact that necessarily takes a string value, this parameter can be equal to , in which case it will pass the check. Thus, the exploitation of this vulnerability made it possible to execute code remotely from the admin panel and gain root access on the device.

SQL injection

We also detected several problems associated with the injection of SQL code.

With the development of smart home software, the introduction of new components and dependencies is inevitable. Yet at the same time, they have to be accommodated in memory of very limited size. As a result, developers have to question the need for each new file in the system so as to avoid unnecessary future outlays on having a larger memory for each device. Therefore, developers of embedded devices often try to reduce, as far possible, the number of executable files and libraries that get installed onto the device. This is probably why Home Center did not have a library for interaction between SQLite and PHP, which could eliminate SQL injection by design errors with the help of prepared statements.

Simplified code sample containing an error

As can be seen in the screenshot, the system developers wanted to avoid SQL injections through the use of a very interesting filtration technique involving the duplication of quotes in the query, and a no less unusual method of accessing the database by running the sqlite3 tool from the command line. However, such filtering turned out to be insufficient because the quotes can still be escaped using a backslash in the first parameter. If such a backslash is inserted, it leads to a breakout from the string context in the second parameter and potential SQL injection in the database query.

In versions older than 4.540, all database queries were modified and securely rewritten using prepared statements.

The “Attack”

Using the vulnerability identified, we managed to retrieve a backup copy from our colleague’s device, in which only one file was of interest to us: the SQLite database file. A careful examination of this file showed it to contain a lot of valuable information:

- Our colleague’s password in cached form with an added salt

- The precise coordinates of the home where the device was located

- The geolocation of our colleague’s smartphone

- Our colleague’s email addresses used for registration in the Fibaro system

- All data about IoT devices (including ones not belonging to Fibaro) that were installed by our colleague at home, with device model, username/password in text form, IP addresses of devices in the internal network, etc.

Note that storing passwords for Fibaro Home Center-integrated IoT devices in text form allows an attacker with access to the Home Center and the SQLite database to gain access to all other devices in the home.

An offline attempt to brute-force our colleague’s password led nowhere, and none of the passwords for the other devices in the home worked for the Home Center control panel. However, we would have been very surprised if such a simple attack had produced a result. As a company, we regularly emphasize the need to use strong unique passwords for each device or service.

If we could have recovered the password from the hash using brute force, or if one of the passwords for the other devices had worked, we could have got inside the Home Center control panel. Then, to elevate privileges in the system, we would have needed to exploit the remote code execution vulnerability described above. To gain access to the device in this case, the owner’s participation would not have been required. But we had to take a different route.

We created a special backup copy in which we placed a password-protected PHP script that could execute any our command. After that, using the relevant cloud functionality, we sent an email and an SMS to our colleague for him to update the software on the device by downloading from the cloud the backup copy that we had prepared.

Our colleague knew straight away that these messages were sent by us. First, he had been expecting an “attack,” and second, our email did not match the standard format used by Fibaro. However, an ordinary user unaware that their smart home is being hacked might not spot the difference in format. As such, our colleague decided to continue the experiment and installed the backup copy.

The web server for executing PHP scripts was run on the device with superuser rights. So after the backup copy was installed by the device owner, we gained access to the smart home with maximum privileges.

Naturally, being decent and responsible people, we did not take any harmful actions in our colleague’s home – with the exception of changing the melody on his alarm clock to indicate our presence. The following morning, our colleague awoke to the soothing tones of drum & bass.

But unlike us, a real attacker with access to Home Center is unlikely to just fool around with the alarm clock. One of the main tasks of the device we investigated is to integrate all smart things so that the home owner could manage them from Home Center itself. A “smart thing” here can be not just a light bulb or kettle, but vital safety equipment: for example, alarms, window/door/gate opening and closing mechanisms, surveillance cameras, heating/air conditioning systems, etc. The havoc a villain could wreak in this situation is the stuff of horror movies, not this article.

Conclusion

In the course of this study, we were able to gain potential access through the cloud to all Fibaro Home Centers by uploading and downloading backup copies, as well as full root access to our colleague’s smart home.

We uncovered critical vulnerabilities on the device itself and in the cloud service. Our findings were reported to Fibaro Group, after which all the vulnerabilities were successfully eliminated.

We wish to thank Fibaro Group for this successful cooperation, and hope that we have helped to improve the security of their flagship product.

Currently, smart home nightmares are confined to horror movie screenplays, but they could soon become a terrifying reality if we do not take sufficient care over what we make and use.