24 April 2020

Threat landscape for industrial automation systems. APT attacks on industrial companies in 2019

- 2019 Report at a glance

- Vulnerabilities identified in 2019

- APT attacks on industrial companies in 2019

- Ransomware and other malware: key events of H2 2019

- Overall global statistics – H2 2019

Attacks on Colombian companies

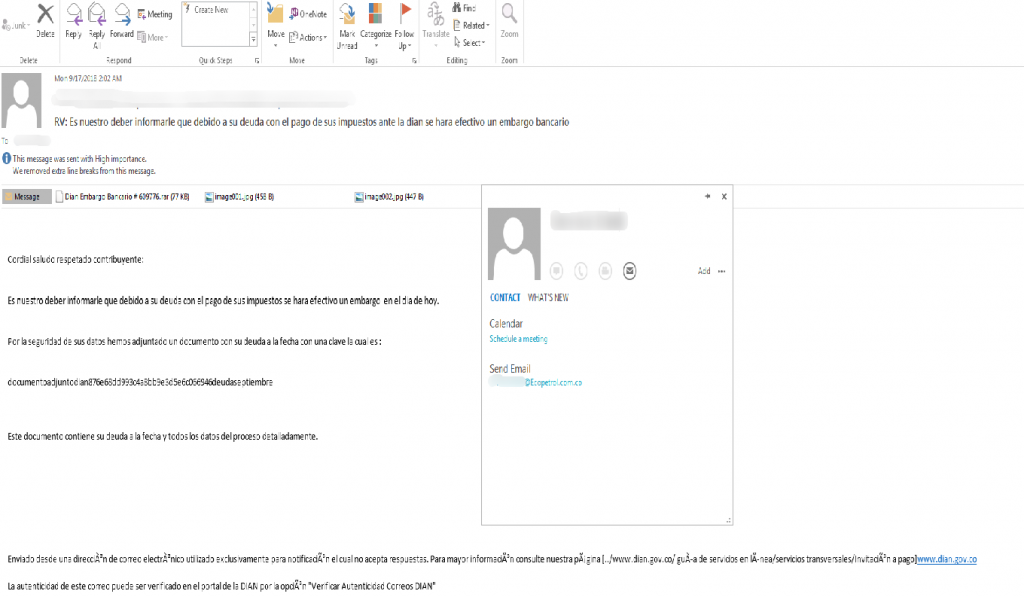

In February 2019, researchers from the 360 Threat Intelligence Center reported continuing targeted attacks on Colombian government institutions and large companies in the financial sector, petroleum industry, manufacturing and other sectors. The attacks were carried out by the APT-C-36 group (aka Blind Eagle). The researchers believe that the group’s members come from South America.

The attackers target the Windows platform. They deliver malware via phishing emails that contain password-protected RAR attachments, which can help evade detection at the email gateway. The decryption password is provided in the message body.

The attachment contains a document with the extension DOC. The document contains an MHTML macro designed to install the Imminent backdoor, which has extensive functionality and is used to gain a foothold in the target network. The researchers believe that the attackers are focusing on strategic-level intelligence and could attempt to steal business intelligence and intellectual property.

Attacks by APT40 group

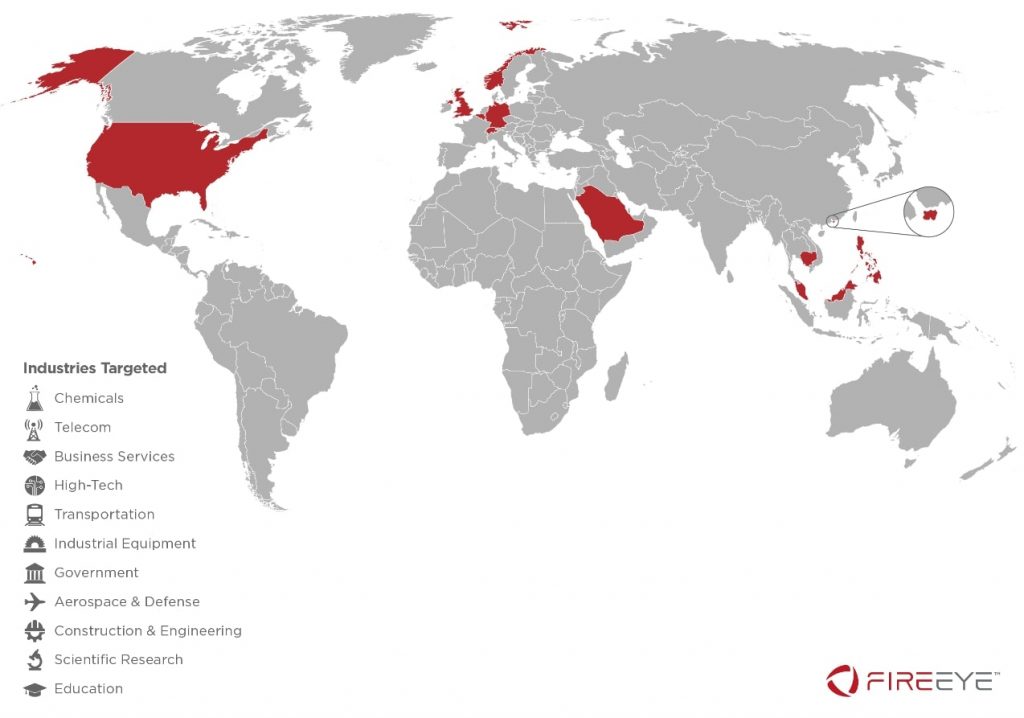

In March 2019, FireEye reported attacks carried out by APT40, which researchers believe to be a Chinese state-sponsored group. The group has conducted operations in support of China’s naval modernization effort since at least 2013. The Chinese cyber-espionage group is also known as TEMP.Periscope, TEMP.Jumper and Leviathan.

APT40 has targeted the engineering, transportation, and defense industries, particularly where these sectors overlap with maritime technologies. FireEye researchers have also observed attacks on targets that are strategically important for China’s One Belt, One Road initiative, including Cambodia, Belgium, Germany, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Malaysia, Norway, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland, the US and the UK.

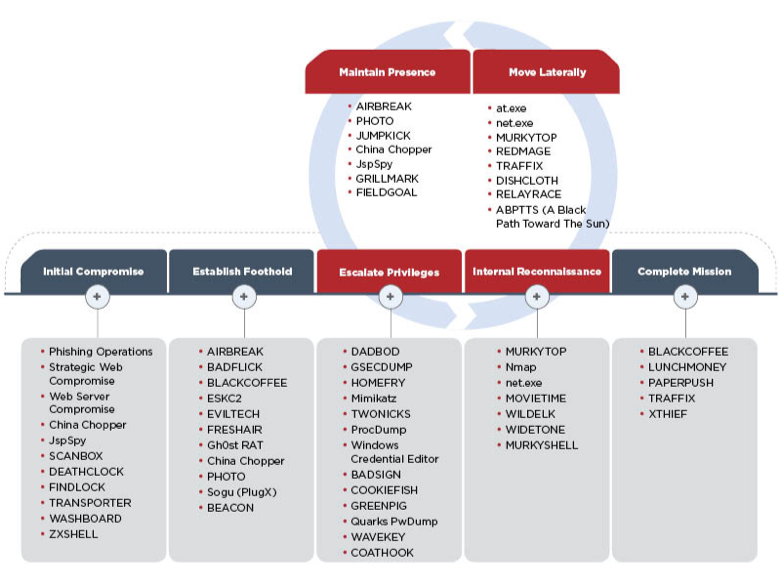

APT40 leverages various techniques for initial compromise. These include exploiting victims’ web servers, running phishing campaigns with vulnerable documents that install both publicly available and custom backdoors. In addition to malicious attachments, phishing emails have been observed to contain links to Google Drive. In some cases, the group has leveraged malicious executables with code signing certificates to avoid detection. It is also worth noting that the group’s arsenal includes web shells (malicious scripts that can be used to control infected machines from outside the network) that are used to gain a foothold in the organization. This enables the attackers to make their access more extended in time and to re-infect systems.

APT40 often targets VPN and remote desktop credentials to establish a foothold in a targeted organization. This methodology is very convenient for attackers, since once the credentials are obtained, they need not rely on malware to continue their attack.

Hexane/OilRig/APT34

On August 1, 2019 Dragos published an overview of attacks entitled Global Oil and Gas Threat Perspective, in which a new group dubbed Hexane is mentioned. According to the report, Hexane targets the oil and gas and telecommunications sectors in Africa, the Middle East and Southwest Asia. Dragos says it identified the group in May 2019, associating it with OilRig and CHRYSENE groups, which are believed to be Iranian. Hexane seems to have begun its activity around September 2018, with a second activity wave in May 2019.

Although no indicators of compromise have been published, some researchers shared hashes in a Twitter thread in response to the announcement made by Dragos that they had identified a new group. An analysis performed by Kaspersky has also identified some similarities between TTPs used in the new wave of attacks and TTPs used by the OilRig group.

In all of these cases, the artifacts used in attacks were relatively simple. The constant evolution of droppers apparently indicates a trial-and-error period, when the threat actor was searching for the best way to evade detection.

The TTPs that Kaspersky can link to the OilRig activity preceding the emergence of Hexane include:

- the trial-and-error process mentioned above;

- using simple documents with macros as droppers, distributed via phishing emails;

- Using DNS-based exfiltration to C&C servers.

The source code of tools used by Iranian attackers, which was leaked through Lab Dookhtegan and GreenLeakers Telegram channels, provides a clue as to the way in which the Hexane group may have emerged. Because of the exposure and leaks, the OilRig group may simply have changed its toolset and continued its operations as usual: this would explain the group’s quick and flexible response to the leaks. Another possibility is that some of OilRig’s TTPs may have been adopted by a new group whose interests are similar to those of OilRig.

Later in August, Secureworks released a report, where they described the toolset of the same group, which they called Lyceum. The report described a phishing document, a first-stage RAT and PowerShell scripts used in attacks.

IBM X-Force analysts believe that the APT34 group (aka OilRig and Crambus) is behind an attack on energy facilities in the Middle East, which made use of data-wiping malware called “ZeroCleare”. According to a report published by IBM, OilRig, as well as at least one other group, likely also based in Iran, used compromised VPN accounts to access machines in at least one case.

In December, Bapco, Bahrein’s national petroleum company, was attacked by a wiper, which was dubbed Dustman. Saudi Arabia’s National Cybersecurity Authority (NCA) released a security alert on the attack. An analysis of the malware showed that Dustman is an upgraded and improved version of the ZeroCleare wiper.

APT33

Attacks by one more Iranian group, APT33 (aka NewsBeef, Charming Kitten, and Elfin) target the petroleum and aviation industries. Recent findings by TrendMicro show that the group has been using about a dozen command-and-control servers for targeted attacks on organizations in the Middle East, the US, and Asia.

The group uses several layers of hosts to obfuscate its real C&C servers.

The malware used by the attackers is relatively simple and has limited capabilities, including downloading and running additional malware.

In 2018, the group attacked tens of thousands of companies, attempting to guess user account passwords by trying several commonly used passwords (password-spraying attacks). According to Microsoft, by the end of 2019, APT33 had narrowed its activity to about 2,000 organizations per month, while increasing the number of accounts attacked in each of these organizations almost tenfold on average. About half of the group’s 25 main targets, ranked by the number of accounts attacked, were manufacturers, suppliers or maintainers of ICS equipment. Microsoft says it has seen APT33 target dozens of industrial equipment and software firms since mid-October. What remains unclear is the hackers’ motivation and which industrial control systems they have been able to breach. Microsoft experts believe that the group is seeking to gain a foothold to carry out cyberattacks with physically disruptive effects.

Symantec has reported that in the past three years, the group has attacked at least 50 organizations in Saudi Arabia, the US and a range of other countries. Symantec experts believe that some of the organizations in the US have been targeted by the group in order to mount supply chain attacks. In one instance, a large US company was attacked in the same month that a Middle Eastern company it co-owns was compromised.

In the wave of attacks in February 2019, APT33 attempted to exploit a known vulnerability (CVE-2018-20250) in WinRAR. The exploit was used against an organization in Saudi Arabia’s chemical sector. Two users in the organization received a file named “JobDetails.rar”, which was likely delivered via a spear-phishing email. It has also been noted that APT33 uses both custom and numerous commodity backdoors, such as Remcos, DarkComet NanoCore, etc.

In August 2019 Forbes and WSJ ran stories on attacks of Iranian hackers on Bahrain’s government institutions and critical infrastructure, drawing parallels with 2012 Shamoon attacks. They also mentioned that in July 2019 hackers had shut down several systems in Bahrain’s Electricity and Water Authority. According to the authorities, that was a rehearsal or demonstration of the vulnerability of heavily secure control systems, which would deliver a significant impact if fully compromised.

Operation Wocao

Fox-IT researchers have reported on the activity of a hacker group, which, they believe, was tasked with obtaining information for espionage purposes. The activity was dubbed “Operation Wocao”. It has the same TTPs as a Chinese group known in the industry as APT20. Its victims have been identified in ten countries – in government entities, among managed service providers and across a wide variety of industries, including Energy, Health Care and High-Tech.

In several cases the initial access point into a victim network was a vulnerable webserver, often versions of JBoss. It was observed that such vulnerable servers had often already been compromised with web shells, placed there by other threat actors.

Operation Wacao actually leverages other groups’ web shells for reconnaissance and initial lateral movement. Then the group uploads one of its own web shells to the webserver. Access through the uploaded web shell is kept by the group as a precaution in the event of losing the other primary method of persistent access, for example in case the credentials for VPN accounts are reset.

In one case, VPN access to the victim’s network was protected with two-factor authentication (2FA) using RSA SecurID software. The group bypassed the 2FA implementation using a technique that Fox-IT believes they had developed independently.

An algorithm patented by RSA is used to generate the password (token code) for two-factor authentication. Each token has an initial generation vector (seed) assigned to it. A new token code is generated once a minute and its value is defined only by the seed and the time at which it is generated.

In the hardware implementation of RSA SecurID, the initial generation vector is reliably protected and can only be obtained by stealing the physical token. However, Fox-IT experts have determined that the RSA SecurID software token only uses the unique key generated for each software installation (and linked to the system’s unique parameters) to validate the token’s import, while the initial generation vector is a unique value that is not linked to the system in any way. According to Fox-IT, this means that the attackers only need to patch one instruction in the RSA SecurID software to be able to use the software to generate token codes valid for any system from which they were able to steal a software token installed on it. Thus, Fox-IT researchers believe that the attackers could have stolen a software token from the victim and used patched RSA SecurID software on their own machine to generate valid two-factor authentication tokens that could be used to connect to VPN.

APT41/Winnti

In August 2019, FireEye reported on the activity of a Chinese group that has been operating since 2012 and is involved in strategic espionage in areas related to China’s five-year economic development plan. Attacked organizations are in healthcare, semiconductor manufacturing, advanced computer software, battery and electric car manufacturing, and other industries. These organizations are located in 14 countries, including France, India, Italy, Japan, South Korea, the UK, and the US.

A distinguishing feature of the group, which was dubbed APT41, is that it combines attacks on various organizations targeted for cyberespionage activities and financially motivated attacks on the gaming industry, in which the group has manipulated virtual game currencies and attempted to deploy ransomware.

The group gained access to Windows and Linux machines on organizations’ networks, stole source code and digital certificates from the machines that were of interest to them, subsequently using the certificates to sign their malware.

APT41 is also known to have embedded their malicious code into legitimate files of gaming companies. The resulting malicious files were signed with those companies’ legitimate certificates. The files were subsequently deployed in other organizations, which means that the group implemented supply-chain attacks.

Among the more interesting aspects of the group’s TTPs, it is worth mentioning that its attacks were highly targeted. Specifically, the unique system IDs of target machines could be checked prior to deploying some of the next-stage malware used by the group. It should also be mentioned that APT41 makes limited use of rootkits and MBR bootkits, which is generally quite uncharacteristic of Chinese APT groups.

An analysis of the time of day when both types of attacks – cyberespionage attacks on companies in strategic industries and for-profit attacks on gaming companies – were carried out showed that the group’s participants engage in the latter type of attacks in their spare time, probably for their personal financial gain. They may be operating under the protection of the authorities.

According to reports published earlier by other companies, APT41 partly overlaps in their activity with Barium and Winnti. FireEye also attributes CCleaner, ShadowPad, and ShadowHammer attacks to APT41.

ESET researchers believe that the APT41 group described by FireEye, which is behind the high-profile supply-chain attacks on the gaming industry, is in fact Winnti. They have determined that the Winnti group continues to upgrade its arsenal and uses a new modular Windows backdoor called PortReuse, which has been used to infect a major Asian mobile hardware and software vendor. ESET has also identified third-stage malware in one Winnti attack on gaming companies – it was a customized version of the XMRig cryptocurrency miner.

Several large German industrial companies, including BASF, Siemens and Henkel, announced in July that they had fallen victim to a state-sponsored hacker group from China. In April, Bayer reported discovering an intrusion. All these attacks may have been carried out by different sub-groups, but what united them was that they all used the Winnti backdoor.

Attacks on the aerospace industry

The European aerospace giant Airbus has suffered a series of attacks mounted presumably by Chinese hackers for the purposes of cyberespionage. In January 2019, the company issued a press release, in which it stated that the company had detected an intrusion into its systems related to the commercial aircraft business, but the incident had made no impact on the company’s commercial operations. Some sources in the company also reported a series of attacks during the previous year.

There have also been reports of hacker attacks on British engine maker Rolls-Royce, the French technology consultancy and supplier Expleo, as well as two other French contractors working for Airbus. According to sources, attacks on contractors enabled the attackers to gain access to VPN connecting these companies with Airbus.

In October 2019, Crowdstrike released a report (later removed from the company’s website), which uncovered one of China’s most ambitious hacker operations. The goal of a coordinated hacking campaign that lasted for many years was to help the Chinese state-owned aerospace manufacturer Comac to build its own airliner C919. The ultimate objective, says Crowdstrike, was to steal intellectual property that would make it possible to manufacture all of the aircraft’s components in China. According to Crowdstrike’s report, The Ministry of State Security (MSS) assigned this task to its Jiangsu Bureau (MSS JSSD). During the period from 2010 to 2015, the hacker team successfully hacked such companies as Ametek, Honeywell, Safran, Capstone Turbine, GE, and others.

According to Crowdstrike and US Department of Justice data, the group, which the researchers dubbed Turbine Panda, enlisted local hackers and information security researchers, including those who are well-known in underground communities. They were tasked with finding entry points into target networks, where they commonly used malware from such families as Sakula, PlugX, and Winnti, searching for confidential information and stealing it.

APT32/Ocean Lotus

According to FireEye researchers, APT32/OceanLotus, a Vietnamese hacker group that has been active since at least 2014 and is known primarily for its attacks on journalists and government organizations, started aggressively targeting multinational automotive companies in 2019 in what is apparently an attempt to support the domestic auto industry. Since February 2019, the group has sent phishing emails to between five and ten organizations in the automotive sector. The group has also created fake domains for Toyota Motor Corp. and Hyundai Motor Co. in attempts to gain access to the auto makers’ networks. It is not known whether these attacks were successful.

According to a Toyota representative, in March the company discovered that it was targeted in Vietnam and Thailand, as well as through its Japanese subsidiary, Toyota Tokyo Sales Holdings Inc. A Toyota official confirmed that APT32 was responsible.