26 October 2021

APT attacks on industrial organizations in H1 2021

This summary provides an overview of APT attacks on industrial enterprises disclosed in H1 2021 and related activity of groups that have been observed attacking industrial organizations and critical infrastructure facilities. For each story, we sought to summarize the most significant facts, findings, and conclusions of researchers, which we believe can be of use to experts who address practical issues related to ensuring the cybersecurity of industrial enterprises.

SolarWinds

A large-scale and sophisticated supply chain attack on SolarWinds’ Orion IT enterprise software was described in our previous APT review. Researchers continued to investigate the case and reported new findings.

New malware families were discovered: one, named “Sunspot”, was deployed in September 2019, when the attackers first breached the company’s network. It was installed on SolarWinds’ build server and was designed to monitor the server for commands that assembled the Orion product. Once an Orion build command was detected, the malware silently replaced a source code file with a file that loaded the Sunburst malware. Another, named “Raindrop”, is a backdoor loader that drops Cobalt Strike, post-compromise, as a means of moving laterally across the target network. Microsoft has published a further analysis of the malware used in the attack, in particular the missing chain in the attack and the sequence of processes leading from the Sunburst backdoor to the execution of the Cobalt Strike loader. The attackers separated these two components as far as possible to evade detection. The research also includes an analysis of additional hands-on-keyboard techniques used by the attackers during initial reconnaissance, data collection and exfiltration, in addition to the broader TTPs published already.

Later, new malware families used by the threat group behind the SolarWinds attack were identified. They include a backdoor called GoldMax (aka Sunshuttle), Sibot and GoldFinder.

Prodaft, a Swiss cybersecurity firm, has published research describing the activity of a group they found and dubbed SilverFish, which they claim was connected with the SolarWinds incidents (they believe multiple groups, each with its own motives, were behind the incidents). The group was responsible for intrusions at over 4720 private and government organizations, including Fortune 500 companies, ministries, airlines, defense contractors, audit and consultancy companies, and automotive manufacturers. An extensive campaign was active between August 2020 and March 2021. Prodaft managed to access one of the group’s C2 servers. It obtained valuable information on the victims and post-exploitation activities from the server. The most unusual activity they discovered was the use of existing enterprise victims as a sandbox for testing malicious payloads for detection with enterprise EDR and AV solutions, with the results of scanning reported back to the server.

Cicada/APT10

In November and December 2020, Symantec and LAC published blog posts about a campaign of an actor known as APT10. One month later, Kaspersky observed new activities from the actor with an updated version of some of their implants designed to evade security products and make analysis more difficult for researchers.

Kaspersky has investigated a long-running espionage campaign dubbed “A41APT” targeting multiple industries, including the Japanese manufacturing industry and its overseas bases, active since March 2019. The attackers used vulnerabilities in an SSL-VPN product to deploy a multi-layered loader that was dubbed “Ecipekac” (aka DESLoader, SigLoader and HEAVYHAND). Most of the payloads deployed by this loader that have been discovered are fileless and had not been seen before. The following malware was observed: “SodaMaster” (aka DelfsCake, dfls and DARKTOWN), “P8RAT” (aka GreetCake and HEAVYPOT), and “FYAnti” (aka DILLJUICE Stage 2), which in turn loads QuasarRAT, a popular open-source remote administration tool.

Andariel

Kaspersky has discovered Andariel activity targeting a broad spectrum of industries located in South Korea, including organizations in the manufacturing, home network service, media and construction sectors, using a revised infection scheme and, in one case, custom ransomware. In April, Kaspersky observed a decoy document with a Korean file name uploaded to VirusTotal. It revealed a novel infection scheme and an unfamiliar payload.

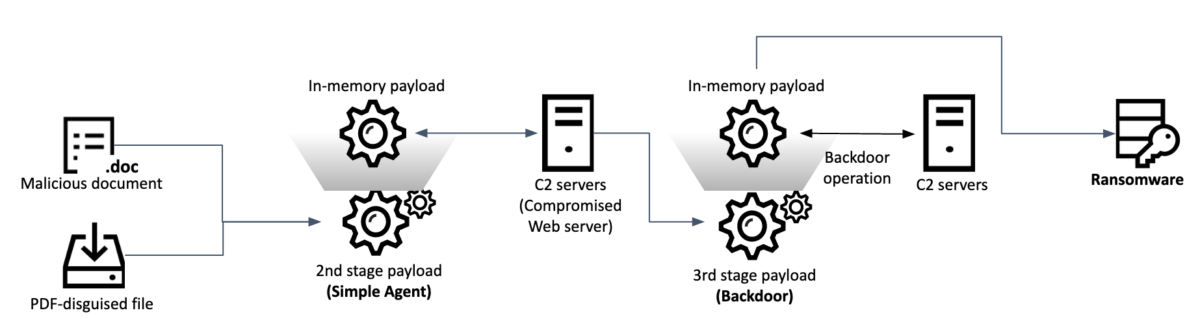

The threat actor has been spreading the third stage payload since the middle of 2020 and leveraged malicious Word documents and files mimicking PDF documents as infection vectors. Notably, in addition to the final backdoor, one victim became infected with custom ransomware, adding another facet to this campaign of Andariel, which also sought financial gain in a previous operation involving the compromise of ATMs.

During the course of this research, Malwarebytes published a report with technical details of the same series of attacks, attributing it to the Lazarus group. After a deep analysis, Kaspersky came to a more precise conclusion in this regard: we believe that the Andariel branch of the Lazarus group was behind these attacks. Code overlaps between the second stage payload in this campaign and earlier Andariel malware allowed for this attribution. Apart from the code similarity and the victimology, the way Windows commands and their options were used in a backdoor shell in the post-exploitation phase is almost identical to earlier Andariel activity.

Chinese-speaking Threat Groups

The Cybereason Nocturnus Team has found spear-phishing RTF documents weaponized with RoyalRoad that deliver PortDoor malware, a previously undocumented backdoor assessed to have been developed by a Chinese-speaking threat actor. Over the years, the RoyalRoad weaponizer, also known as the 8.t Dropper/RTF exploit builder has been included in the arsenal of several Chinese-speaking threat actors such as Tick, Tonto Team and TA428, all of which use RoyalRoad regularly for spear-phishing in targeted attacks against high-value targets.

According to the phishing lure content examined, the target of the attack was the CEO of the Rubin Design Bureau, a Russian defense contractor that designs submarines for the Russian Navy.

A series of ransomware attacks with unclear purposes hit Taiwan organizations in April and May 2020. Affected organizations include CPC Corporation — a state-owned petroleum, natural gas, and gasoline company and the largest gasoline supplier in Taiwan, Formosa Petrochemical Corporation, Chunghwa Telecom and, reportedly, organizations in the semiconductor industry. Given the highly targeted nature of these attacks, their lack of sophistication and the lack of contact information for ransomware payments in some of the ransomware variants, as well as the fact that the campaign was launched just one week before the president’s inauguration in Taiwan, some believe the true motive behind these attacks may be not financial gain but something else, such as causing disruption or drawing the attention away from other activity. On May 15, the Investigation Bureau of the Ministry of Justice (MJIB) released an investigation report stating that Winnti or another closely related group was suspected of being behind these attacks.

ReverseRat attacks in India and Afghanistan

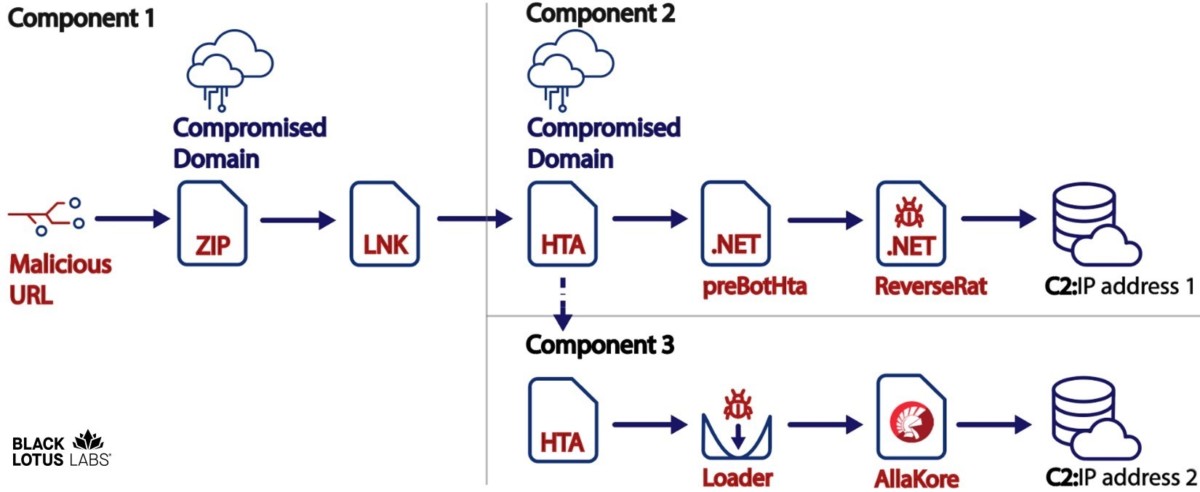

Lumen’s Black Lotus Labs has discovered an attack in which the majority of victims are located in India and a small number in Afghanistan. The attack involves a new remote access Trojan called ReverseRat. Victims include a government organization, a power transmission organization, and a power generation and transmission organization somewhere in “South and Central Asia” (the country remains undisclosed). The actor behind this campaign has operational infrastructure hosted in Pakistan and researchers assume that it also originates from that country. The infection chain of this campaign and its TTPs are correlated with last year’s campaign called Operation SideCopy.

A multi-step infection chain results in the victim downloading two agents: one resides in-memory (ReverseRAT), while the second is side-loaded (AllaKore), ensuring the threat actor’s persistence on infected workstations. The original URLs that are the sources of the entire infection chain have not been found, but they are likely sent in targeted emails or messages, as observed in the actor’s similar campaigns.

Operation Spalax

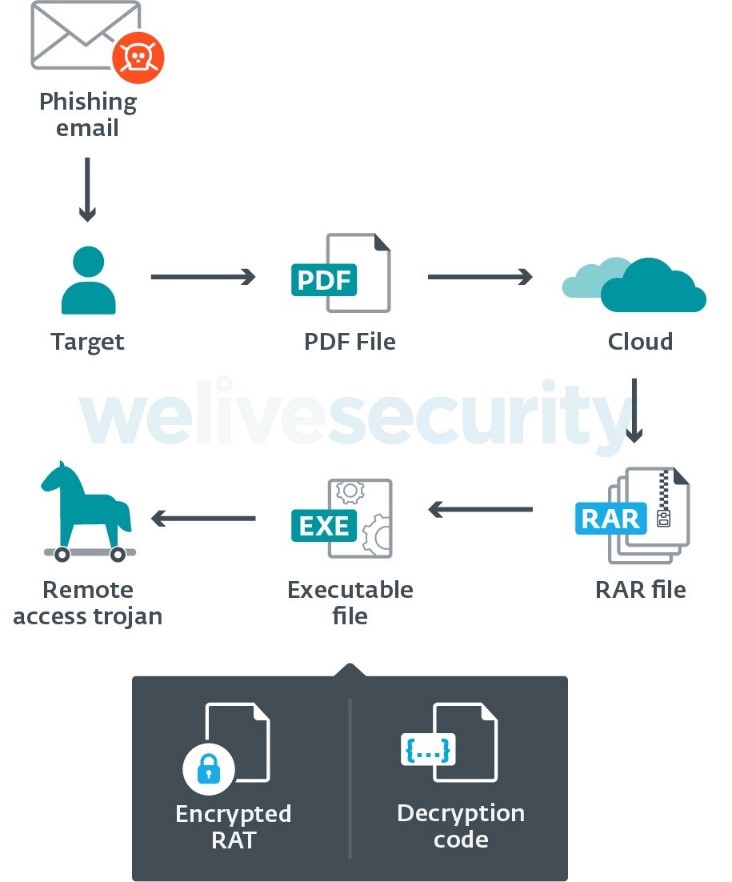

Researchers have uncovered attacks targeting Colombian organizations, including government institutions and private companies, particularly in the energy and metallurgical industries. The ongoing attacks, dubbed “Operation Spalax”, install remote access Trojans, most likely to conduct cyber-espionage activities

The attacks observed in 2020 share some TTPs with those described in earlier reports on groups targeting Colombia, for example, the QiAnXin report and the TrendMicro report. The phishing emails used in the attack lead to malicious files being downloaded. In most cases, these emails have a PDF document attached to them, which contains a link that the user must click to download the malware. The files that are downloaded are regular RAR archives containing an executable file. The payloads installed by operation Spalax are popular cybercriminal RATs: Remcos, njRAT and AsyncRAT. Several droppers have been observed that are variants of a packer which uses steganography. These droppers have previously been used with Agent Tesla samples, but in this case, they contained no Agent Tesla payload.

New Lazarus activities uncovered

Following up on an earlier investigation into Lazarus attacks on the defense industry that used the ThreatNeedle cluster, Kaspersky discovered another malware cluster named CookieTime, used in a campaign that was mainly focused on the defense industry. We detected related activity in September and November 2020, with samples dating back to April 2020. CookieTime has a different structure and functionality, compared to known malware clusters of the Lazarus group. This malware communicates with the C2 server using the HTTP protocol. It uses encoded cookie values to deliver requests to the C2 server and to fetch command files from the C2 server. The C2 communication takes advantage of steganography techniques used in files exchanged between infected clients and the C2 server. The data transferred is disguised as GIF image files that contain encrypted commands from the C2 server and command execution results. Kaspersky researchers had a chance to look into the command-and-control script as a result of working closely with a local CERT to take down the threat actor’s infrastructure. The malware control servers are configured in a multi-stage fashion and only deliver the command file to valuable hosts.

ESET researchers have discovered a previously undocumented backdoor, dubbed “Vyveva”, used to target a freight logistics company in South Africa. The backdoor is designed to collect information from the victim’s computer and exfiltrate data. The malware communicates with the C2 via the Tor network. Researchers attribute this to Lazarus based on similarities with the threat actor’s previous operations and samples.

RedEcho/ShadowPad

Recorded Future researchers have observed an increase in targeted intrusion activities against India’s power sector since early 2020. They attribute the activity to a threat actor dubbed “RedEcho”. Since mid-2020, there was a steep rise in the use of the infrastructure they track as “AXIOMATICASYMPTOTE”, which encompasses ShadowPad C2 servers.

Kaspersky has also researched the 2020-2021 attacks in India in involving the ShadowPad loader and infrastructure described by Recorded Future. A broader geography of victims was discovered based on telemetry data. Victims of these attacks include critical infrastructure organizations. The toolset used in these attacks includes an updated ShadowPad loader dubbed “ShadowShredder”. It was described in a private APT report. Still, attribution remains vague, as ShadowPad was originally known to be used by the BARIUM/APT41 group (aka “Winnti”), but since 2019 it has been used by multiple other Chinese-speaking APT actors such as Tick, CactusPete, and IceFog.

Zebrocy

In March, researchers observed a cluster of activities targeting Kazakhstan with Delphocy – malware written in Delphi that has previously been associated with Zebrocy, supposedly a subgroup of Sofacy. The lures were Word documents purportedly created by a company named Kazchrome, a mining and metallurgical company and one of the world’s largest producers of chrome ore and ferroalloys. Six Delphocy Word documents that appear to be related to this cluster have been found in total. All of the documents contain the same VBA script that drops a PE file. Out of the six Word documents observed, two appear to be authentic uploads to VirusTotal by victims originating from Kazakhstan.

Zebrocy is already known to have targeted Kazakhstan’s industrial companies with VBA documents back in 2018, so it seems to keep this tactics.

Attack on Iranian centrifuges

On April 10, there was a power blackout at Iran’s Natanz nuclear facility, affecting not only the site’s main power distribution equipment but also its backup systems. Initially, Iranian officials confirmed neither that there were casualties nor that the facilities had suffered damage. However, later it was acknowledged that some centrifuges had been damaged and that the “small explosion” had “damaged sectors [which] can be quickly repaired.” Iran’s foreign ministry has blamed Israel for sabotaging the country’s main uranium enrichment facility, although this has not been confirmed.

RATs targeting aerospace

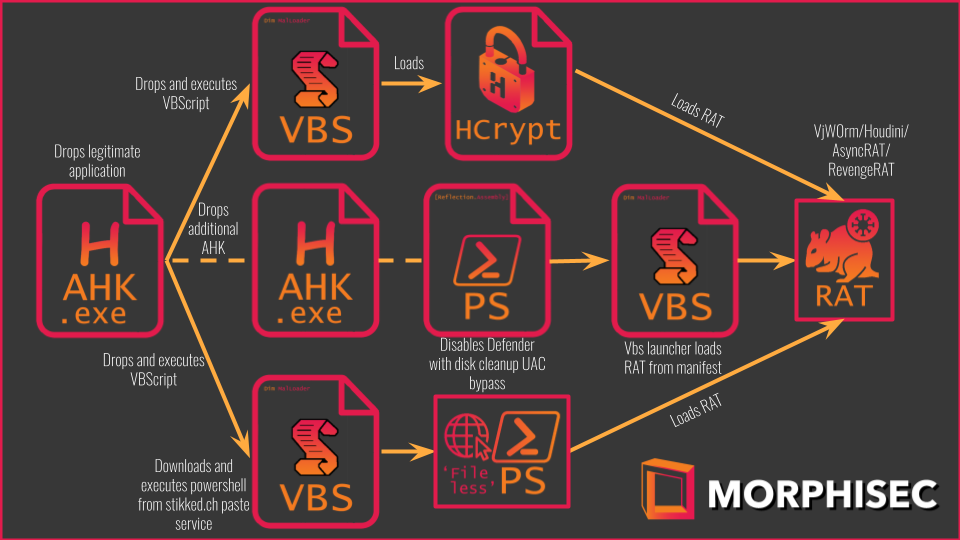

Researchers have warned of an ongoing spear-phishing campaign targeting aerospace and travel organizations, using a new and stealthy malware loader to deploy a series of RATs such as LimeRAT, RevengeRAT, and AsyncRAT. The attackers lure their victims with images masquerading as PDF documents that contain information relevant to the target’s industry.

Attackers use remote access Trojans for data theft, follow-on activity, and additional payloads, including Agent Tesla, which they use for data exfiltration. The loader is under active development and is dubbed Snip3 by Morphisec.

Gelsemium

The APT threat actor Gelsemium, a cyberespionage group active since 2014, is believed to be responsible for recent supply-chain attacks against targets in China, Japan, Mongolia, Taiwan, North and South Korea, and various Middle Eastern countries. The targets include governments, religious organizations, electronics manufacturers and universities. The supply chain attack was first described in an Operation NightScout article. The attack compromised the update mechanism of NoxPlayer, an Android emulator for PCs and Macs that is part of BigNox’s product range with over 150 million users worldwide. In these campaigns, ESET researchers found a new version of Gelsemium’s complex and modular malware, as well as additional tools such as the OwlProxy and Chrommmebackdoors.

Conclusion

So what are the most important conclusions that can be drawn from an analysis of publicly available information about APT attacks on industrial organizations in H1 2021?

First and foremost, that APT researchers have identified no cases of product damage, equipment failure or other (perhaps even graver) physical consequences of attacks on systems that are part of industrial enterprise OT networks. It is worth mentioning the incident at a water treatment plant in Florida in this respect: since it is highly likely that none of the APT groups was involved in that incident, we did not include it in this report. As for the incident at the Natanz nuclear plant, we were able to find no reliable data in public sources indicating that this was a cybersecurity incident.

The next most important conclusions, in our view, reflect today’s overall trends in the evolution of the threat landscape for organizations of various sectors, types, and profiles, highlighting common challenges faced both by the threat research community and by experts whose work includes ensuring the actual cybersecurity of IT and OT infrastructures.

We can state that:

- We increasingly see tools formerly associated primarily with criminal attacks being included in the toolset of APT groups.

- Social engineering remains the most popular initial penetration method not only for cybercriminals, but also for APT groups.

- APT groups often don’t bother to exploit zero-day vulnerabilities: the infrastructure of their potential victims is full of old, well-known flaws that are actively exploited by other attackers (one example is attacks that exploit vulnerabilities in SSL VPN gateways).

- The widespread use of commercial malware is no longer an indication of a purely criminal nature of the attacks.

- A zero-day vulnerability being exploited in an attack is no longer a clear sign of an APT.

- The popularity of ‘commercial’ malware among APT actors can be explained, apart from purely pecuniary considerations, by the natural wish to remain unnoticed or at least unrecognized, lost amongst the multitude of criminal attacks.

- It is worth noting, however, that other things than the toolset can also be borrowed from cybercriminals for that purpose, such as the infrastructure (we will cover this in our future publications) and even strategy. In H1 2021 (as we predicted), an APT group followed the steps of ExPetr operators in trying to disguise their activity as ransomware.

- Categorizing the diverse tools and infrastructure used in attacks in order to find out who is behind the various attacks (something information security experts call “attribution”) and compiling an encyclopedia of the various known groups remains a difficult task. Despite the large amount of work that has already been done by numerous researchers, finding a consensus often proves impossible. Professional cybersecurity threat actors leave few clues, and it often proves impossible to sort out their crimes in the virtual world without ‘the Attorney General’s consent’. This is demonstrated admirably by research into the notorious series of SolarWinds related attacks.

Kaspersky ICS CERT

Kaspersky Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team is a global project of Kaspersky aimed at coordinating the efforts of automation system vendors, industrial facility owners and operators, and IT security researchers to protect industrial enterprises from cyberattacks. Kaspersky ICS CERT devotes its efforts primarily to identifying potential and existing threats that target industrial automation systems and the industrial internet of things.